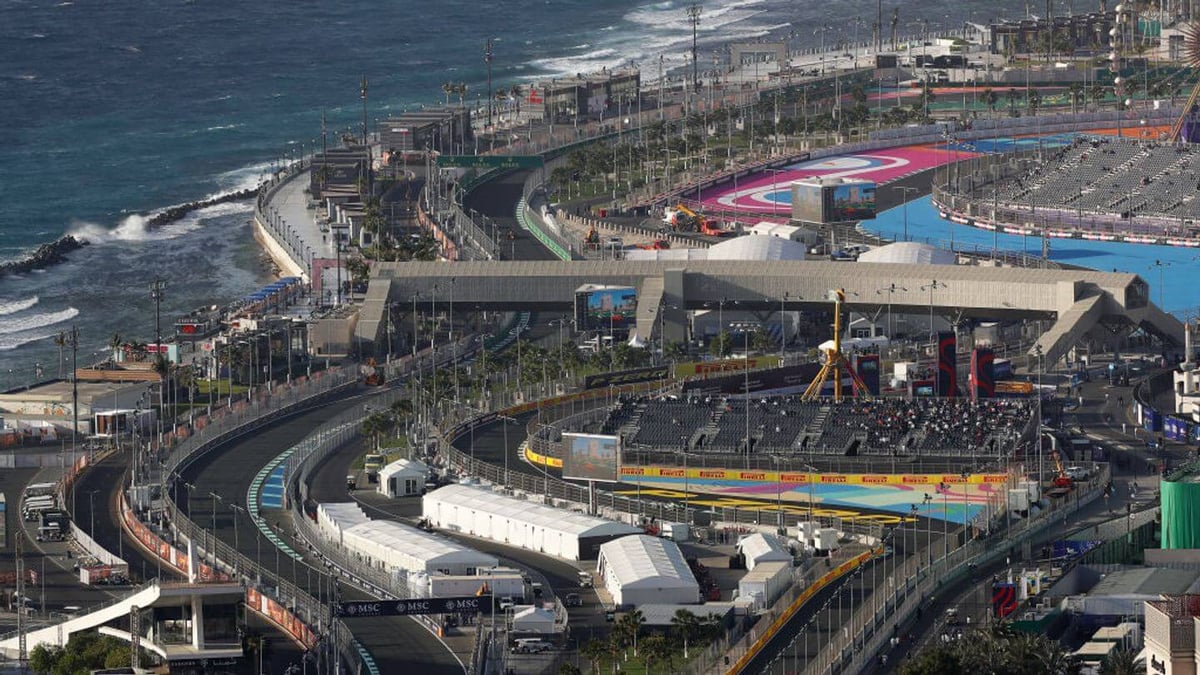

Fast and unforgiving, racing around the Jeddah Corniche Circuit remains one of Formula 1’s least predictable grands prix.

The Saudi Arabian Grand Prix still resists easy categorisation. Run under floodlights on the Red Sea coast, the race takes place on a circuit that looks temporary but behaves nothing like a conventional street track.

Walls sit close, visibility compresses at speed and mistakes tend to arrive without warning. Four seasons in, the Jeddah Corniche Circuit remains one of the calendar’s most demanding venues, not because it is unfamiliar, but because it refuses to settle into predictable patterns.

As is so often the case, the goings-on at the coastal street circuit will have a crucial impact on the drivers’ standings at the end of the season. You’ll find that the drivers’ championship odds on betting sites in Saudi Arabia are frequently reshaped by events in Jeddah, such is the drama on a track where drivers must decide whether to hold their nerve in close quarters or throttle back and accept compromise.

Jeddah’s position as the fifth round of the 2026 season only sharpens that tension. By the time Formula 1 arrives in Saudi Arabia, early form has been established and initial narratives are already under scrutiny.

The circuit becomes a stress point for those assumptions, a place where confidence can be reinforced or abruptly undone, and where a single misjudgement can carry consequences far beyond one race weekend.

What makes the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix compelling is not novelty. It is the way a circuit designed at speed continues to test the limits of modern Formula 1 cars, tyres and decision-making, even as teams grow more familiar with its demands.

Why Jeddah still feels like an outlier on the Formula 1 calendar

Jeddah does not fit neatly alongside other street circuits. Unlike Monaco, it does not rely on low speed and precision alone. Unlike Baku, it offers few extended breathers between high-commitment sections. Instead, it sits in an uncomfortable middle ground, combining the proximity of barriers with average speeds more commonly associated with permanent circuits.

At nearly 6.2 km in length, the Jeddah Corniche Circuit is the second-longest track on the calendar and features 27 corners, more than any other venue used by Formula 1

According to Pirelli, drivers spend close to 80 percent of the lap at full throttle, a figure that underlines how little margin exists for hesitation. Average lap speeds hover around 250 km/h, making it the fastest street circuit the sport has ever raced on and second overall only to Monza.

That combination creates a rhythm that few circuits replicate. Drivers are asked to commit fully through blind, high-speed sequences where visual reference points arrive late, and recovery options are limited.

The circuit encourages flow but punishes disruption. The uncomfortable reality is that when something goes wrong, it tends to do so at pace.

This is why Jeddah has never fully normalised within the paddock. Even as familiarity grows, teams continue to approach the weekend with caution, aware that the circuit’s demands are unlike anything else on the schedule.

Fast enough to blur vision at the Corniche Circuit

The defining challenge of Jeddah lies in how speed interacts with visibility. Several corners in the opening sector are taken flat or near-flat yet are bordered by concrete walls that restrict sightlines and amplify consequences. Drivers turn in before they can see the exit, trusting that nothing unexpected lies ahead.

That characteristic has prompted repeated discussion within the garages about risk tolerance. In 2023, Max Verstappen described parts of Jeddah’s first sector as more dangerous than Spa-Francorchamps, pointing to blind sections where an incident ahead would offer little warning to following cars.

The Dutchman’s comments were framed not as criticism, but as an acknowledgement that the circuit operates close to Formula One’s comfort threshold. When Verstappen, a driver most at ease when operating on the limit, makes an observation of that nature, it carries weight.

That edge has already had consequences in Jeddah, most notably in his run-ins with stewarding at the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix, which further demonstrates how little margin exists when incidents unfold at speed.

The demands placed on the car mirror those faced by the driver. Mechanical grip, aerodynamic stability and confidence over kerbs all matter, but none can fully offset the need for commitment. Setups that perform consistently elsewhere can feel exposed here, particularly as track conditions evolve through the evening sessions.

Jeddah rewards decisiveness. It also exposes hesitation. That balance is what keeps the circuit on edge, even after multiple visits.

From first contact to fine margins in team preparation

Teams arrived in Jeddah in 2021 with limited reference points and a conservative mindset. The circuit was new, built at speed and bordered by unforgiving walls. Early weekends were defined as much by restraint as by ambition, with wary engineers prioritising stability over outright performance.

As data accumulated, approaches evolved. Jeddah began to reward aerodynamic confidence more than mechanical compromise, with long sequences of fast corners quickly exposing instability. Cars that slide or snap at medium speed elsewhere tend to feel nervous here, where correction windows are narrow.

Qualifying has taken on outsized importance as a result. Track position matters on most street circuits, but at Jeddah it often dictates the tone of an entire weekend. Overtaking opportunities exist, particularly into Turn 1, but the risk attached to close racing through blind sections encourages calculated aggression rather than constant attack.

By round five, teams are no longer experimenting freely. Jeddah forces them to go all in on what they believe works, bringing unresolved weaknesses into heightened focus.

Adjustments made without redesigning the circuit

Formula 1 and the FIA have responded with targeted changes rather than wholesale redesign. Ahead of the 2023 event, several measures were introduced following driver feedback.

Walls were repositioned at corners, including Turns 8, 10, 14 and 20 to improve sightlines. Kerbs were lowered to reduce the risk of cars being unsettled if they ran wide at speed. The chicane at Turns 22 and 23 was tightened to moderate entry speed, and rumble strips were added in multiple areas to help drivers remain within track limits.

These adjustments have improved visibility and reduced some risk, but they have not altered the circuit’s fundamental character. Jeddah remains narrow, fast and unforgiving. The aim has been to manage danger rather than remove difficulty, reflecting Formula One’s broader approach to circuit safety.

Tyres, strategy and the limits of control

Strategic variation in Saudi Arabia has historically been constrained by the circuit’s layout. Across multiple editions of the race, a one-stop strategy has proved most effective. The 2025 event was a one-stopper again, with leaders typically moving from medium to hard once track position mattered more than theoretical pace.

Pirelli’s decision to introduce softer compounds has added nuance. For Jeddah, Pirelli has gone one step softer in its allocation, with C3 as Hard, C4 as Medium and C5 as Soft, explicitly to create more strategic options rather than lock teams into a single rhythm. Increased grip can narrow operating windows through the fastest sequences, where temperature sensitivity becomes decisive over one lap.

Safety cars remain a constant consideration. Formula 1’s own pre-race metrics have repeatedly treated a Safety Car here as close to inevitable, with a stated Safety Car probability of 100% and a pit stop time loss of around 20.1 seconds, which is why teams weigh “waiting for a neutralisation” against the risk of being trapped in traffic.

If you are watching closely, Jeddah often reveals which teams trust their cars under pressure and which remain cautious when control begins to slip.

Why the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix still alters the competitive picture

Looking ahead to round five in 2026, expectations will be set rather than speculative. Saudi Arabia lands at the point where early pace is understood, yet the competitive picture remains fragile enough to swing on a single compromised session.

Margins compress quickly. With only 168 metres from pole to the Turn 1 braking point, track position can shift before the race has even found its rhythm.

The other destabiliser is interruption. With Formula 1 repeatedly listing a Safety Car probability of 100% here and pit-stop loss sitting around 19–20 seconds, one neutralisation is almost guaranteed to influence strategy again in 2026.

In that context, Jeddah does not just reward speed. It rewards teams that stay decisive when the weekend stops behaving like a model.

An interim venue with lasting significance

The Jeddah Corniche Circuit was never intended as a permanent home for the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix. Race organisers have said the event is expected to remain in Jeddah until at least 2027 while work continues on the planned Qiddiya venue. Yet Jeddah continues to matter because of what it reveals about modern Formula 1.

It exposes the limits of aerodynamic confidence, the importance of visibility at speed and the fine balance between spectacle and risk. And the intended successor underlines the point: Saudi Arabia has released plans for a purpose-built Qiddiya circuit featuring 21 corners and around 108 metres of elevation change, designed by Alex Wurz alongside Hermann Tilke.

Until the final race is run here, Jeddah will remain a reference point rather than a placeholder. Not because it is comfortable or settled, but because it continues to demand answers Formula 1 cannot ignore.