It has now been 138 days since Formula 1 cars last raced competitively and at the most optimistic estimation it will be another 78 days before the five red lights are next extinguished.

When the paddock departed the Yas Marina Circuit in early December 2019 no-one could have foreseen the current situation engulfing Formula 1, pushed into this position by the outbreak and spread of a global pandemic. A sport that has a reputation for carrying on regardless has been halted in its tracks for the first time in its 70-year history. After the disastrously inept handling of the ultimately cancelled Australian Grand Prix Formula 1 has largely been decisive and progressive with subsequent decisions, most prominently the delay to the new regulations, the retention of 2020 chassis for 2021, and the shifting and extension of a factory shutdown period. All of these decisions will help ease the financial burden on Formula 1 teams, who each have varying short- and long-term motives, along with different income worries.

Nevertheless, that income is predominantly sourced from key areas via the commercial rights holder, most notably prize money, broadcast revenue and race fees, complemented by individual sponsorship packages. They are largely dependent on grands prix taking place. And the longer a grand prix does not take place then ostensibly the bleaker the situation becomes. It means that attention, at some stage, must turn to getting back to racing. But what are the main challenges facing the championship’s bid to return?

At what point does sport become acceptable?

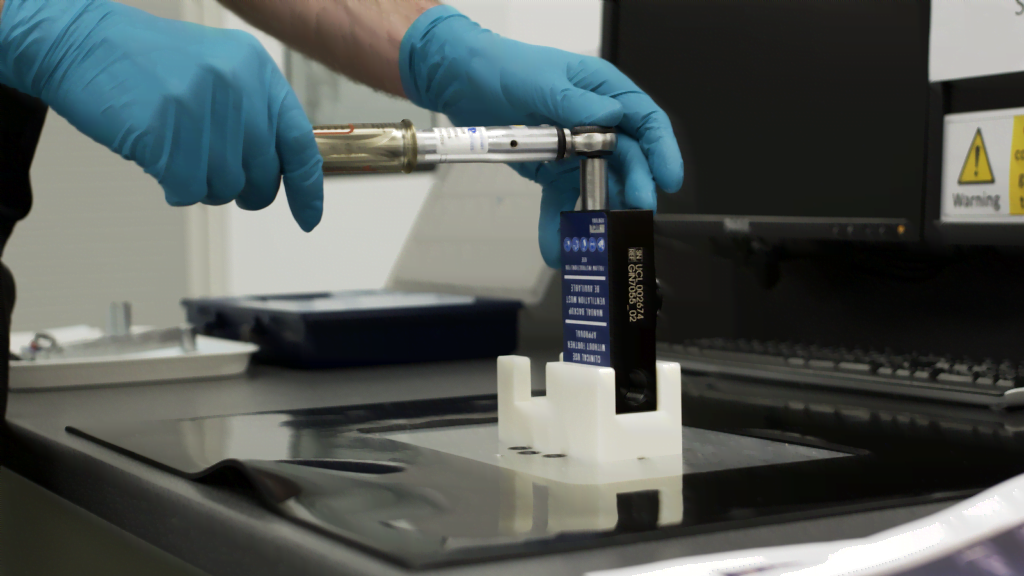

As the hours developed during the build-up to the Melbourne event there was a notable change in attitude. Very quickly the idea of a large-scale gathering taking place for the purpose of sport became increasingly – and correctly – questioned. At that stage the situation in Italy had deteriorated (joining China and Iran) while other countries had progressed past the point of no return, though the effect had yet to be truly felt. COVID-19 was only named on February 11, and only declared a pandemic on March 11 – the Wednesday of the Australian Grand Prix weekend. Attitudes were very quickly changing. Sport, across the world, was halted. It was rapidly perceived as frivolous and unimportant. Formula 1 teams swiftly put their efforts into assessing how their skills and resources could assist the COVID-19 fight. Project Pitlane was born. Mercedes HPP repurposed its entire Brixworth engine facility to produce 10,000 CPAP breathing devices while elsewhere ventilators have been co-designed, Personal Protective Equipment has been produced, and other projects have been bubbling away. It has given Formula 1 a lot of goodwill.

But sport is business, not to mention a branch of entertainment. Every governing body and commercial rights holder in any sport is striving to work out how it can return. On a wider scale there is the oft-unspoken question of what matters more: saving people from Coronavirus or preventing long-term damage to the economy. At some stage the thinking is likely to pass from the former to the latter courtesy of more scientific data, financial predictions from various government-linked departments, not to mention the potential for the wider public to eventually want to get on with life. Therefore, to apply that to Formula 1, at what point will business interests emerge as the priority over the human element? Formula 1, after all, has shareholders it has to appease.

“I think it’s important that we only go back to go racing once we have certainty when it comes down to protective equipment, to the number of tests for people, that this is all in place and available to people that actually need it and that we are not the ones burning these tests or this material just to go back racing,” said McLaren team boss Andreas Seidl.

It is a sage point. No sporting entity will want to be the first to be seen to be taking away vital equipment – whether that is protective equipment or tests – from those for whom it is essential, such as front-line healthcare workers. But if tests are being used for people who are responsible for getting a multi-billion-dollar sport underway then how big is the public image risk? This doesn’t apply just to Formula 1 but also to football, rugby, tennis, cricket, American football, basketball etc etc. The employment of hundreds of thousands of people will hang in the balance the longer the delay goes on. It almost feels crass to have to weigh up the various pros and cons when lives are at stake.

What about the travel restrictions?

It is highly likely that any sport that returns will first do so behind closed doors. Some experts have indicated it may not be until late 2021, or until a vaccine is found and widely available, that large-scale events can return. But even before considering a closed-to-the-public Formula 1 event there is one aspect that is a problem: travel restrictions. Formula 1’s global nature and appeal has previously been a key asset. The ability to travel across the world and hold different style events in the course of just a few days is something few other sports can offer – not to mention the logistical mastery that has built up over the years. For example, last September Formula 1 started off in rural Belgium, hurtled down to just-outside-Milan in Italy, flew across to a growing city for the Singapore night spectacle and saw out the month adjacent to the Black Sea in Russia. But this strength is now a weakness.

Football leagues have proposed completing the current season within a confined space, whether that is one stadium or certain arenas, it is nonetheless within the same territory, governed by the same respective jurisdiction. Those needing to fulfil potential Premier League fixtures are already in England. Ditto the Bundesliga and Germany, or Serie A and Italy. Formula 1 does not have that luxury. Most Formula 1 operations are based in England but there are factories in France (Renault), Italy (Ferrari/AlphaTauri), Switzerland (Alfa Romeo) and Japan (Honda), not to mention suppliers and personnel who are currently in other countries. A quick chat with a colleague regarding the number of different nationalities working in Formula 1 got us to around 50 – if not more. A handful of countries had to be avoided to/from Australia in order to prevent the risk of detainment in a stopover hub while Italian teams brought forward getting its personnel out in case tighter restrictions were imposed. Currently there are travel restrictions in place in vital territories while some countries have indicated that borders may not open for several months. “All but essential travel” is the current instruction given by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office – F1 may find a loophole but so long as this is in place it poses problems. It poses a risk for personnel if they leave as they may not be able to swiftly return. The wording of “all but essential travel” bluntly means there is a safety risk, and teams have stressed that the health and well-being of employees is the priority. Any edict advising against travel also invalidates vast swathes of insurance policies, creating another headache for which a solution may not be forthcoming. And if restrictions are eased then personnel – along with equipment (some of which took several weeks to reach Britain, via Dubai, after the Australia cancellation) – may need to be quarantined for an unknown period of time.

How would a behind-closed-doors event work?

This is a big unknown for which there are no concrete answers as it depends on uncertainties and variables. Formula 1 has never before run without spectators (insert joke here about certain grands prix) and the intention to hold Bahrain with only essential personnel was ultimately canned. Who counts as essential? There are many different strands of a grand prix and several divisions could be swiftly cut.

Without any spectators there would be no guests and thus any marketing departments could be struck off the list. A few hospitality staff would also be left at home. And, while it is not what anyone in our industry would want, the media (and a swathe of photographers) could quickly be prohibited – that would reduce three hundred or so from the headcount, along with media centre staff and other operatives. Broadcasters might also be banned, bar those who need to rig the circuit and install camera points for the world feed, though this would then ostensibly lead to negotiations over finances and contracts. Down the political rabbit hole we go. Given the size of some broadcast teams this would reduce the headcount while a portion of FOM employees who work on-location could also be shifted remotely to its Biggin Hill centre. Finding out your role isn’t essential (and this is not limited to FOM), in an environment full of egos, may also be a fun development…

But even accounting for this potential reduction the size of the paddock would still be large. Each race team features around 60 personnel and thus the basic Maths brings this up to a minimum of 600. Very few of these could be cut. Why? They need to run and maintain two Formula 1 cars. If they weren’t regarded as essential then they wouldn’t be present in the first place. Once you add in Pirelli, Honda, the FIA employees, marshals (needed for motor-racing), a medical crew and other assorted personnel then very quickly the headcount rises to a minimum of 1,000. This is before the likes of Formula 2 and Formula 3 are even taken into consideration (though it is likely they would be left at home). The situation regarding those championships is a talking point for another day.

Even if an event is held behind closed doors it risks being prohibited on account of the number of people involved. In France a large gathering, banned until mid-July, counts as more than 100 people. In other countries a figure has not been placed but it will be discretionary. Allowing an F1 event to take place, even behind closed doors, may lead to questions from other sectors or individuals over why their industry or business is unable to take place, for example.

Getting the essential paddock personnel into and out of a race track, and housing them, is also another aspect: where do they stay? What transport means do they use? Can they be distanced from the rest of the population for an entire event? And, if as in Australia, there is a positive test, what happens then? Scratch the surface and an array of issues are uncovered.

Will promoters want it?

Each Formula 1 promoter is different, has different ambitions, different opinions, with different requirements. We can only sympathise both with them and with Chase Carey, whose inbox must have a number of emails best described as ‘yikes’. There are a range of parties who need satisfying, compromises that must be made, and not all of them (maybe any of them) will get what they want. Many have sold tickets and while a postponement provides leeway financially for now, the likelihood of a behind-closed-doors event will likely prompt a refund, as would a cancellation altogether. For those events that attract a large crowd the notion of running behind closed doors may be unpalatable financially, meaning a compromise will have to be reached with Liberty Media. Why pay an enormous race fee – with no guarantee of any ticket sales – without some benefits either in the immediacy or over the next few years?

Another aspect to consider – and this is of less importance – is the perspective from broadcasters. Viewing figures, and therefore revenue, will be down in 2020 but even if and when racing resumes it is fair to assume that other sports will restart at a similar time. It is not unreasonable to therefore expect an overload of options for fans. There could be a situation where a Formula 1 race, a sequence of high-profile football matches, a tennis Grand Slam, a golf tournament, a major horse race, a cricket test, a rugby international, not to mention myriad of other motorsport and motorcycling competitions all take place on the same weekend, if a three- or four-month window opens at the end of 2020. It would be unprecedented in sporting history. What do you watch and how do you watch it? There may be compromises ahead.

How, when and where will Formula 1 return? At the moment it sadly feels that we are through the looking-glass…